Love the parasite you're with - the entertaining life of unwelcome guests from flea circuses to Aliens

Alien vs. Predator/IMDB

Anna-Sophie Jürgens, Australian National University and Alexander Maier, Australian National University

Bloodsucker, leech, tick – few things have a reputation worse than parasites. But these biological hangers-on also have a comic cultural history.

In biology, a parasite is an organism that lives on or in a host organism and gets its food (or other benefits) from (or at the expense of) its host. Scientists have just documented the oldest known example of a parasite-host relationship – a nutrient stealing worm over 500 million years old.

Due to their complex and often hidden life cycles, parasites seem to appear suddenly. They thrive in oozing wounds or are transmitted via explosive diarrhoea. No wonder parasites occupy a vivid role in our cultural imagination.

In fiction and popular culture, parasitic characters appear as a metaphor for the threat and spread of disease. They infiltrate human bodies and transform them into monsters, like Dracula. Or they act as extraterrestrial biological weapons like in the Alien saga. The quintessential parasite narrative – per 2019’s Oscar-winning Parasite – showcases it as a physiological, psychological and social threat. But they’ve also played for laughs.

Read more: A 515 million-year-old freeloader: this nutrient-stealing marine worm is the oldest known parasite

Humbugs

Italian showman Louis Bertolotto’s “extraordinary exhibition of industrious fleas” from the early 1820s is the first documented flea circus. It featured a 12-piece flea orchestra playing audible flea music, a Great Mogul Flea (with harem!), a ballroom with flea ladies and frock-coated gentlemen dancing a waltz, a mail coach drawn by four fleas (with a cracking whip) and a reenactment of the Battle of Waterloo including Wellington, Napoleon and field marshal Blücher – all played by miniature warrior fleas.

Today, traditional flea circuses can still be found. Flohzirkus Birk and his fleas have entertained small crowds at Oktoberfest in Munich for decades. Humans play fleas and other insects in the Cirque du Soleil show Ovo – leaping through a day in the life of bugs.

In Germany, the flea circus still entertains.

The flea fiction literary genre exists for those who prefer to use their own imagination. It includes humorous 19th century texts such Hans Christian Andersen’s The Flea and the Professor and German Gothic writer E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Master Flea, both of which feature tame flea companions and collaborators.

The genre also includes flea porn, which features the little bloodsuckers in all kinds of interesting perspectives. An example is the The Autobiography of a Flea (published anonymously in 1887).

My funny parasite

Use of the word “parasite” predates its biological label.

In 1755, Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary defined parasite as “one that frequents rich tables, and earns his welcome by flattery”.

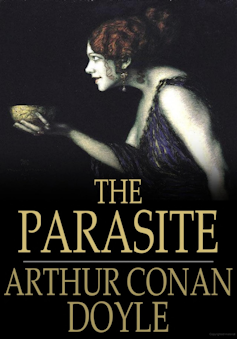

The comic heritage of the parasite shimmers through Honoré de Balzac’s 1847 novel Le Cousin Pons (which had the working title Le Parasite) and Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Parasite, first published in 1894. The latter is about a professor who is turned into a clown, “the laughing-stock of the university”, by a mysterious person, parasite-like influencing his mind and behaviour.

In our recent journal article, we expanded on the work of philosopher Michel Serres and literary scholar Enid Welsford to discuss the parasite as a cultural force. Our paper – a fairly rare collaboration between a biological scientist and a humanities scholar – also looked to more contemporary examples such as the hilarious parasitic remote control in Tim Burton’s 1988 film Beetlejuice.

Beetlejuice looks like a morbid clown with green hair, heavy makeup and a stripey suit. He is a supernatural creature whose job is it to help recently deceased adjust to their eternal afterlife. In this in-between space, Beetlejuice performs what Michel Serres defines as a parasitic communication role: making “productive and creative noise”. By forcing his “hosts” to act differently, this parasite transforms the relationship between two parties and invents a new logic and cohabitation.

In 1988’s Beetlejuice, the central character occupies an in-between realm and acts as a parasitic clown. IMDB

Do gooders

By pushing boundaries and exploring notions of self, parasites are a cultural force and source of comic inspiration. What does it feel like to be a leech? How does the host feel? Where is the line between the two bodies?

There are comic scenarios and narratives hidden in anxieties of involuntarily shared identities. In biology, the sustained and intimate relationship between parasite and host challenges the concept of individual boundaries. The distinction between host and parasite becomes blurred and they form a new entity altogether.

Human louse (Pediculus humanus Linnaeus) bears an uncanny resemblance to the monsters in Alien when viewed under the microscope. Shutterstock

It might come as a surprise that the appreciation of parasites in the arts took place long before biologists acknowledged their contribution. Only in recent decades have parasites been recognised as stabilisers of ecosystems and drivers of evolution and biodiversity.

Their footprints can be seen in genetics, epidemiology and medicine; and a better understanding of parasites has significantly increased our appreciation of them. Exploring the cultural imaginarium of the parasite and its comic dimensions pays tribute to the many positive aspects of parasites.

Whether we like it or not, pathogens like parasites are around us and inside us. They determine us biologically and they influence our cultural norms.

Delving deeper into the cultural world of parasites brings to light droll artistry: from funny domesticated creepy crawlies to clown parasites and dark villains.

Anna-Sophie Jürgens, Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Popular Entertainment Studies and Science in Fiction Studies, Australian National University and Alexander Maier, Professor of Biomedical Science and Biochemistry, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.